Iceland is an interesting country for building an airline. Despite a small population of 387,000 people, its privileged location between two huge economies (North America and Europe) gives the country a fantastic geographical endowment for any hub carrier.

This leaves it in a unique position where a country of its size has two network airlines: Icelandair and PLAY.

Icelandair is the incumbent carrier and can be considered the country’s flag carrier, with a decades-long history. Meanwhile, PLAY was founded during the COVID-19 pandemic with a scope of being a discount alternative for Transatlantic travel, much as WOW air did, some years prior.

WOW, some members of which now compose PLAY’s management, failed prior to the pandemic, which prompted some questions on the viability of having two healthy network carriers in Iceland. Yet PLAY’s main pitch upon its launch two years ago was precisely doing what WOW did right (narrowbody discount flying) and avoiding its major mistakes (particularly going to a very ambitious growth, including the incorporation of widebodies).

And the results of both airlines in the second quarter of 2023, released in prior weeks, may point in the direction that indeed this market setup might work — at least during the Summer season.

Icelandair

Icelandair was the first of the two to announce its results for the quarter, presenting a net profit of USD13.656 million, over an income of USD414.18 million.

The airline is not only focused on passenger transportation, as it has two other major business units, Icelandair Cargo and Loftleiðir Icelandic, the latter providing leasing services.

According to the group’s report, the cargo unit had a negative impact in the bottom line, while Loftleiðir continued to «deliver strong profitability». We will keep our focus on the passenger business, to make the comparison with PLAY fairer.

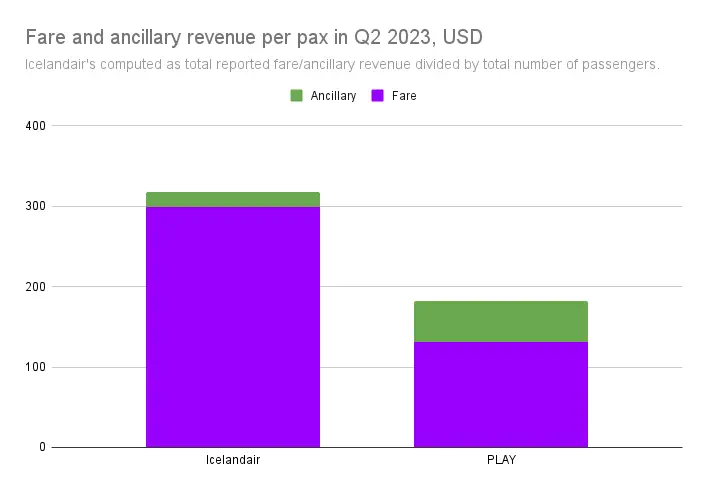

Passenger revenue amounted to USD352.7 million. Of these, USD330.1 million came from airfares and USD22.6 million from ancillaries. Icelandair does not disclose the isolated results from the passenger business unit. However, its reported RASK, at USD8.57 cents, was higher than CASK, at USD8.18 cents.

PLAY

After putting its Transatlantic hub online during the second quarter of last year, this has been the first full second quarter with Transatlantic operations.

The airline registered a net loss of USD4.1 million over revenues of USD73.1 million. Given its nature as a low-cost carrier (LCC), the gap between fare revenue and ancillary revenue is smaller; approximately USD51.3 million in the former and USD20 million in the latter.

While PLAY does have some cargo transportation, albeit almost irrelevant in proportional terms, their clear focus is championing passenger transportation. And for that, increasing volumes is fundamental. The number of aircraft in their fleet grew from four in the same quarter in the last year to ten. And capacity in ASKs practically doubled, with a 99% growth.

How their numbers compare

Despite all of this growth, both airlines improved both their load factors and their unit revenue, which is a very positive sign that the market is ”healing” from the depressed years of international travel during COVID-19.

To paint this promising picture is the earnings season in the United States’ airlines. With a strong economic outlook, Americans are more inclined to travel abroad, which has been worsening (or improving) airlines’ results, depending on their exposure to domestic/international travel.

And the Transatlantic market has been a direct beneficiary of this. According to AirInsight, Frontier Airlines directly mentioned demand to Europe in justifying lower earnings.

With this, both Icelandair and PLAY are surfing on higher yields despite this higher capacity. Icelandair reported a 7.8% increase in RASK over a 17% growth in capacity by ASKs and a 25% growth in traffic by RPKs.

Given its scale-up, figures at PLAY naturally look more impressive: a 13% growth in RASK despite growing ASKs by 99% and RPKs by 126%.

Yet, Icelandair was more profitable than Icelandair. Even if PLAY’s unit cost is considerably lower than its competitor’s, Icelandair managed to achieve higher unit revenues, which ultimately made the difference.

An important caveat when comparing the two airlines — which reflects on higher cost — is that Icelandair operates less dense aircraft, as it markets Saga Premium, its own Business class. Its Boeing 737 MAX 8, for instance, has only 160 seats, in comparison to low-cost carriers, which may put up to 189 within the same aircraft.

This does not mean that Icelandair is necessarily 35% less efficient than PLAY — part of it is a function of having less seats per flight.

By the same token, it means that, by having a Premium cabin, it can charge more from passengers who want a better experience. This also reflects in Icelandair’s unit revenue — considerably higher than PLAY’s.

Observing by the average fare and average ancillary expenditure per passenger, not much changes, largely because the average stage lengths of the two airlines are relatively similar. While Icelandair registered 2,960 km in the second quarter (with data from Cirium’s Diio Mi application, as Icelandair did not report it), PLAY registered it at 2,902 km.

Observing by the average fare and average ancillary expenditure per passenger, not much changes, largely because the average stage lengths of the two airlines are relatively similar. While Icelandair registered 2,960 km in the second quarter (with data from Cirium’s Diio Mi application, as Icelandair did not report it), PLAY registered it at 2,902 km.

With these numbers, Icelandair has returned to consistent positive margins after the pandemic crisis, and it expects this position to stay for the rest of the year. It has reported a 5% EBIT margin in the second quarter, and it is guiding the margin for the full year to be between 4 and 6%.

In the long term, Iceland’s largest airline is targeting to have its EBIT margin at 8%. And if Transatlantic demand does not recede in the next number of years, it will have a positive agenda in this direction. Earlier this year, it announced the incorporation of new Airbus A321neo to replace its aging 757 fleet.

By 2024, it expects to have incorporated another three 737 MAX and to have phased out one 757, according to its fleet plan.

PLAY, meanwhile, should not see a growth nearing 99% into 2024. Its CEO, Birgir Jónsson, said in the press release the second quarter saw «the end of our initial ramp-up phase concluding with the delivery of our tenth aircraft in early June».

The executive described that PLAY has «now reached the necessary operational scale after a very steep growth period for the last two years.» As such, the airline seems to believe it has sufficient volumes to support its hub as a profitable operation. For the coming years, it is in «preliminary negotiations» to add another A321 to its fleet for Summer 2024 and another four in 2025. From now, growth will be slower.

Both take the prize

To answer the question in this article’s title, which of the two won? The answer, much as it may disappoint, is both of them have had good second quarters for each one’s context. Both are carrying momentum into the third quarter, historically (for Icelandic airlines) the most profitable of the year.

Icelandair, the incumbent carrier, is able to reduce cost pressures with a growing footprint of next-generation jets. PLAY, the growing LCC, has seemingly achieved economies of scale to run its operation profitably.

The rest of the Summer thus looks very promising for now. However, as usual in Europe, it remains to be seen on how will they fare during Winter, when Transatlantic traffic generally falls sharply.

It is also important to remember that Icelandair survived during WOW air’s most ambitious years (although it did posted a loss in the peak of irrationality in 2018). WOW, in turn, was profitable «until the point where they introduced the widebodies», as Jónsson — who himself worked at the airline — told Aviacionline last year.

For now, Iceland is returning to 2019 levels of airport movement. Year to date, according to Isavia, the country is very close to pre-pandemic levels of traffic. Whether it will return to the 2018 «miracle» levels is unclear — in that year Iceland saw almost 10.5 million passengers, versus 7.9 million a year later and 6.8 million in 2022.

But the prospect of this small country having two sustainable airlines in the long term now looks better than five years ago.