Maltese aviation will change from March 30 next year: after almost fifty years of continuous operations, Air Malta will cease to exist. However, on the following day a new airline, using Air Malta’s assets and also State-owned, will take over the operations.

The maneuver, taken with the apparent consent of the European Union, takes a page out of the Italian government’s book; a very similar path was taken when transitioning from Alitalia to ITA Airways, with shutting one down and starting another (with a different name) on the next day.

This, of course, is an adaptation to the European Union’s rules: given the strict norms on State aid, a government cannot indefinitely support a failing business without justification.

KM Malta Airlines plc, as the new company will be named, is expected to receive an EUR350 million investment from the funding, the Times of Malta reported. Of these, EUR50 million will be working capital, the rest being directed at purchasing assets such as Air Malta’s slots in Gatwick and Heathrow, as well as three of the aircraft the dying airline currently operates.

Air Malta’s fleet is currently composed of eight aircraft — two Airbus A320 and six Airbus A320neo, according to Planespotters.net — and the plan is keeping the entirety of the fleet in the new airline.

Does Malta really need a flag carrier?

Connectivity, in particular for an island that is reliant on tourism, will always be paramount. Upon presenting the «new» carrier, Prime Minister Robert Abela said that «we cannot be dependent on foreign airlines».

Patriotism, of course, has always played a role in building (and maintaining) failed airlines afloat. In Portugal, the government’s allusion to TAP as representing the modern-day «caravels» became folkloric upon the renationalization-and-privatization novela built around it.

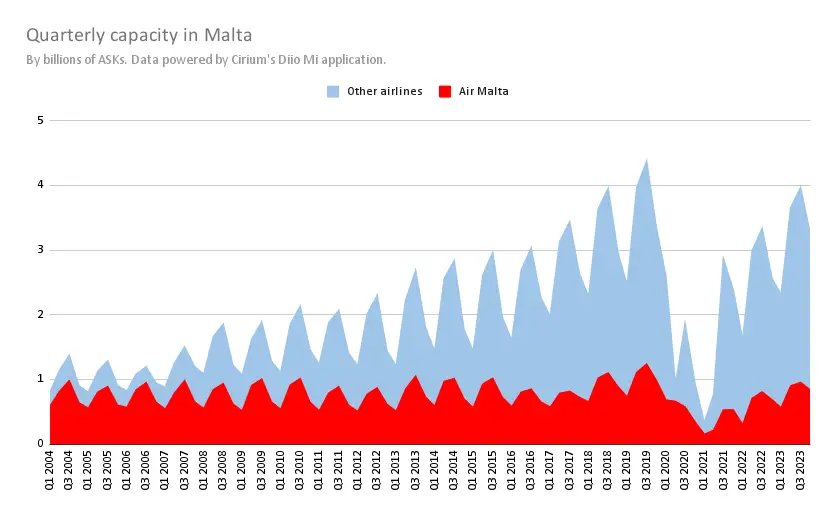

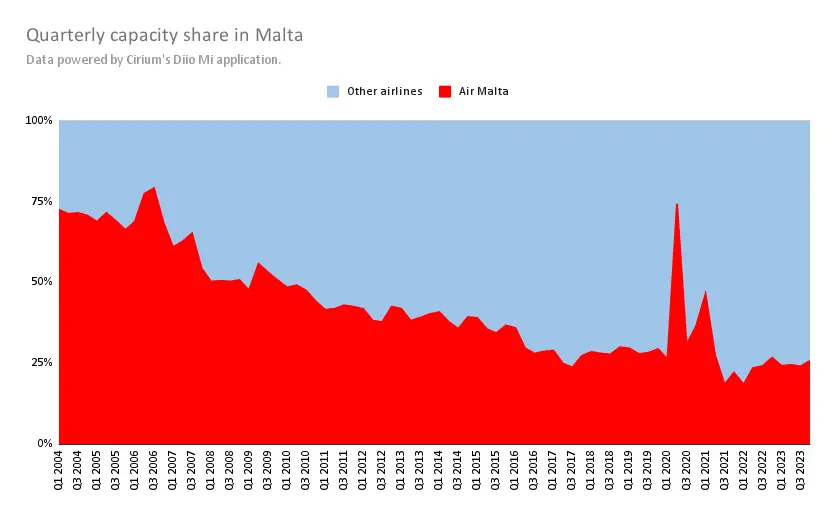

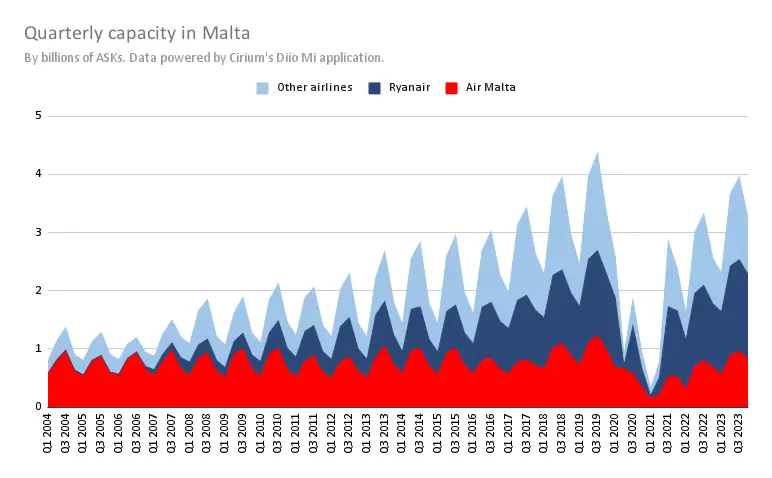

But reality shows Malta is already dependent on foreign carriers, and it has been for years now. The national aviation market grew at a very high speed in the last two decades. However, Air Malta remained stagnated. According to data by Cirium’s Diio Mi application, Air Malta’s capacity in 2023 measured by ASKs is 6% higher than in 2004; ASKs for all airlines serving the country grew by 213.9% in the same period.

This process can also be visualized by means of the capacity share. Air Malta held almost three quarters of the capacity to and from Malta in the first quarter of 2004; by 2023, this number had dropped to around one quarter.

Malta’s plan, meanwhile, is unlikely to change this course. The new airline will fly to 17 destinations — according to the Times of Malta, that figure reached 37 in 2019.

According to the government, that will not mean the new airline will shrink even further. A PowerPoint presentation by the government reported by the Times of Malta says that in the 2024/2025 financial year, KM Malta Airlines plc should carry 2.02 million passengers, versus 1.99 million in the 2019/2020 year for Air Malta.

Increased productivity would be drive such gains (6,874 flights versus 8,357 in 2019/2020), as well as higher load-factors.

The reality is Malta is nowadays much less dependent on Air Malta than it was in the past. Taking a more aggressive path (with public funds) would very likely never be allowed by the European Union in the first place.

This is different than saying that Air Malta is not important at all. In a statement, the Malta Chamber of Commerce, Enterprise and Industry remarked «the vital strategic importance of operating a national airline efficiently».

«The projections presented yesterday by the Minister for Finance acknowledge the unique challenges related to our airline’s size and its markets, which also emanates from Malta’s peripherality to the European continent», said the Chamber, which further «[emphasised] the vital importance of sustainable, uninterrupted air connectivity for Malta, to cater for both business and social exigencies, such as flight operations related to healthcare and Just-In-Time provision of critical medicines.»

A very important point was raised by the Chamber: much as low-cost carriers (LCC) represent a crucial part of air connectivity to Malta today, it is not negligible, from the perspective of an island, that most of these airlines do not carry cargo.

In 2012, a decision of the European Commission considered the peripherality argument (amongst other points) to allow Malta to give a restructuring aid to Air Malta. But eleven years and a pandemic later, it is clear the restructuring did not work, although the airline did attempt downsizing. The Times of Malta reported that fifteen years ago, the airline employed 1,400 people for a fleet of nine aircraft. The new airline should have 400 with one airplane less.

Yet this clearly has not been sufficient. Air Malta is already under threat given its very small scale: to have competitive costs having less than ten aircraft when competition has hundreds is a difficult proposition for any airline. This makes efficiency even more of a mantra, if the new airline is to prosper. It is paramount to have a competitive cost structure, passed on to competitive fares, to make viable routes others would not (or do not) fly.

This proposition can particularly work in main airports, where low-cost airlines do not operate from.

Even so, competition has grown in these airports, too. In the second quarter of 2004, according to Cirium, Air Malta operated 38 routes from its main base (for the sake of simplicity, in this analysis only routes operated twelve times or more in a quarter will be considered in any case). Of these, 13 had competition, not necessarily in the same airport.

If we extrapolate that network to the present day just as another visualization exercise — and excluding routes for which the regulatory situation would be unclear or a no-go –, competition would have grown to 25 of the 35 possible routes. That considers routes operated by other airlines at least 12 times during the second quarter of 2023, according to Cirium’s schedules.

By the same token, KM Malta Airlines plc’s new network will also face competition in eleven of the 17/18 routes it has planned — the number of routes could change depending on the slots it manages to keep in some airports.

Of the six routes the new airline will drop, meanwhile (Geneva, Lisbon, Naples, Nice, Palermo and Tel Aviv), there is competition in four; two, Nice and Palermo, will remain without service, should competitors not take over the gap.

In the current European market, where legacy airlines have a commanding lead in their own markets and LCCs are highly disruptive through their cost base, it is all the more imperative to be efficient.

The Times of Malta remarked, in an editorial, that while the market would take care of most of the gaps left, should Air Malta leave the market completely. But that «national pride is powerful, and few people want to see national brands disappear».

Air Malta’s brand, in time, could well be used by the new airline. This could happen after its owner — the Maltese government — put it for sale in a competitive auction, much as ITA Airways did when purchasing the Alitalia brand.

At least in the announcement of the new airline, the newspaper remarked, there were no grandiose plans of setting up a hub or dreaming of Transatlantic flights. But it still remained cautious with the future, despite the promises by the government of efficiency and a viable airline.

Could Malta Air be the solution?

In 2019, the Maltese government and Ryanair signed a deal whereby the Irish group purchased Malta Air, not to be confounded with Malta Air or the new Malta Airlines. Through the transaction, Ryanair acquired a Maltese air operator certificate (AOC).

The move would allow Ryanair to shift a number of its aircraft into the simpler Maltese framework, as well as leaving local employees to pay their taxes only in their base countries, something that was not possible when the group’s fleet was entirely Irish-registered.

Malta Air did not change Ryanair’s effective aircraft allocation in Malta — as in 2019, it still has six 737s based in the country — but it underscored the group’s commitment to the market.

In fact, highlighting Ryanair’s capacity in the country (graph below) may well illustrate the advance of competition into Air Malta’s turf.

From a daily flight from London/Luton and three weekly rotations from Pisa, the Irish group grew to be the largest airline in the country. In the last quarter of 2023, according to Cirium’s Diio Mi application, Ryanair is offering 1.021 million seats to and from the country, against Malta Air’s 583.5 thousand.

In a 2022 interview to the Times of Malta, Ryanair’s Group CEO Michael O’Leary remarked that «I think Ryanair’s investment in Malta Air means there is now an alternative» to Air Malta, while remarking Air Malta is not much competition to the Irish group and that the State-owned airline served «high-cost» airports.

But the Irish executive said «we do not want to threaten Air Malta, we want to see Air Malta survive. Competition between airlines is good for consumers and is good for tourism in Malta».

Indeed, there are two fair points raised: first, that Air Malta currently serves «high-cost» airports, Ryanair’s nickname for the major hubs in Europe. In the third quarter of 2023, over half of Air Malta’s ASKs touched airports Ryanair does not serve, which are not necessarily major hubs but rather airports that do not provide low charges and/or short turnarounds, vital to their business model.

Without Air Malta, Maltese customers would be able to reach Brussels nonstop, but only Charleroi and not Zaventem; they could get to Milan, but through Bergamo or Malpensa and not Linate. Amsterdam would not be reachable nonstop anymore.

The second point is the one of the competition. While Ryanair may offer lower fares than other airlines in Europe, it would be a natural reaction of any rational economic player to raise prices, should capacity (supply) go down. Competition is the best antidote against high prices.

But for these connections — and the current price environment — to continue existing, KM Malta Airlines plc will have to be efficient. In the press conference announcing the «new» airline, Finance Minister Clyde Caruana said the government planned to find a «strategic partner» to improve the company’s governance.

Air Malta (or Malta Airlines) going forward

This solution, while seemingly ambitious (to end bailouts to Air Malta), should be understood not necessarily from the cynical point of view of political accommodation, but rather from the peripherality argument.

While ITA Airways set the precedent for Malta, the former was clearly more questionable (is there not any airline that would take over long-haul flights in Italy?). Not only Malta is an island, it is also much smaller than its Northern neighbor. The European Union acknowledged that in that 2012 decision and it probably did the same when negotiating this process, which Corriere della Sera said was much less severe in its conditions than it was with Alitalia-ITA.

And such an investment has to be put into context, too. EUR350 million would mean, considering the 2021 Census population, EUR673.64 per person in Malta. That is more than was spent in TAP’s pandemic bailout — just over EUR300 per person — or at ITA Airways, at just below EUR23 (obviously ignoring previous subsidies/bailouts).

One could ask whether this is something that, at least partially, could not have been done with private capital, as the national budget is limited (ie, what is the opportunity cost of spending this amount in keeping the national airline alive). The government seems to be considering to recover part of this amount down the line, with a potential sale of a minority stake.

But that is a matter for Maltese politics to solve. And apparently for their part, whether an airline is needed or not, that seems to be out of the question. Few are the voices against one; as it happens, as an island Malta needs aviation more than almost any other European country.