There is still a lot running under the surface regarding Aerolineas Argentinas’ vaccines and flights. There’s more under the tip of the iceberg. Some time ago we wrote an article in which we explained that, for the cargo volumes being handled, the use of the Airbus A330 and its hold is adequate and economically reasonable.

But there are hypotheses that arise from time to time and it would be a good exercise to contrast them. The goal is to bring some clarity to the situation and try to have a better understanding of some concepts before elaborating cost hypotheses that emerge from our imagination or a quick Google search. Let’s start.

Hypothesis: A freighter is cheaper.

Just a while ago I came across this thread, which attempts to explain the uneconomical nature of AR flights. Lots of goodwill, very well written. But with a fatal mistake.

Me nació contarles, haciendo números, cuánta plata se está desperdiciando por cada vuelo que Aerolíneas Argentinas hace a Rusia a buscar la vacuna Sputnik V. Arranco hilo con datos puros y duros primero. pic.twitter.com/Iaos8JJ5pR

— Peperino Pomoro #ARASanJuan @ 127.0.0.1 (@peperinop) January 27, 2021

As many people indicate in the same thread, some costs are missing but in the grand picture of the total cost, we can give it as valid: U$S 240.000. One of the errors is useful to me and I take it as valid on purpose: the fuel cost is calculated at full load, which is already wrong just for the outbound leg, but that gives me room to include depreciation, wear, and tear, travel expenses. We assume that the cost of salaries exists whether we fly or not, that there are no hotel expenses because the characteristics of the operation do not allow it and we have more or less compensated the small expenses around. The fatal error in the calculation is in the reference parameter of the cost per kilo transported. It has four problems:

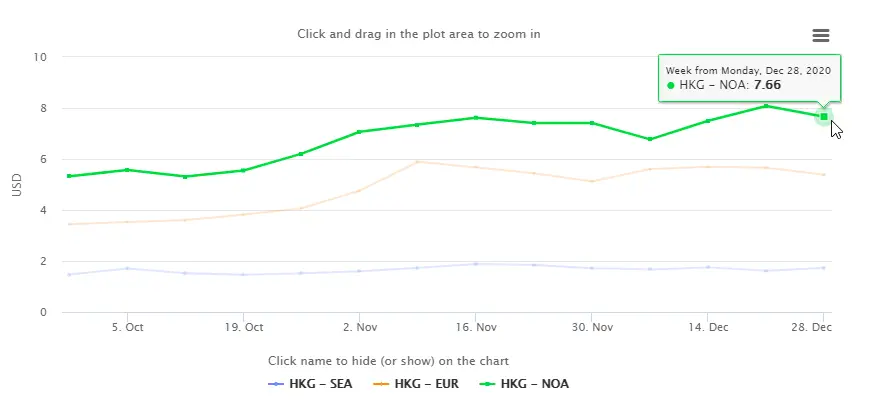

1- It is outdated: It takes as reference a maximum average value of U$S 4.50 based on a 2009 World Bank document. The updated TCA index as of December 2020, at the second peak of demand of the year and with the first waves of the vaccine distribution effort, is significantly greater (taking the higher value of the average, as it was originally done).

Source: TACIndex.com

2 – It is not a valid parameter: As shown in the graph, the route with the TAC Index of 7.66 dollars per kilogram transported is the one that covers Hong Kong and Nowra, a logistics center in Australia. The chart also highlights the routes from Hong Kong to Seattle and Europe. Essentially, because these cities have established permanent logistics air bridges where, in essence, whoever needs to transport goods between these two destinations will just have to find space in the hold of one of the operators serving that route. I take my little box to a counter in Hong Kong, it is picked up by a colleague in Seattle. It is simple and straightforward.

There is no way that the cost will be the same for a route that is already established, operational, and marketed on the basis of frequencies that are scheduled and known in advance -which allows a company to bring competitive delivery times and therefore hire a logistics solution that allows it to meet them- than one that is built together ad-hoc based on the customer demand. Predictability will always be a key ally in cost control. Particularly when it comes to attracting potential customers to take advantage of hold space on scheduled flights. This does not exist in a non-established city pair.

Obviously, this is the situation between Ezeiza and Sheremetyevo. There is no such city pair, nor other customers among which to distribute cargoes. There is no logistics line that would amortize the carrier’s cost by dividing it among customers who take advantage of the capacity offered. There is no corner where to put a small box because there is no counter that reads «Argentina».There is no friend with a car in Moscow who is willing to do us a little favor.

It is harder to talk about the predictability and the possibility of dividing costs with other cargoes when, due to issues that depend on the laboratory or the forwarder (the logistics operator that takes the vaccines out of the laboratory, packs them under the adequate conditions for transport and takes them to the apron so that the aircraft can load them), it is necessary to change the date of the operation, as it happened with the third flight. Every single extra time the aircraft is available when it could be doing something else but is immobilized for reasons unrelated to the freighter’s operation, you are going to be charged for it even if it is not actually flying. Basically because if it had no cost, the most reasonable thing to do is to ground an An-225 and wait until is full. Depending on the vaccine production rate, it would take weeks.

To give a foolish but clarifying example: that is why it is cheaper to travel by train than by private car. The origin, intermediate stops, and destination are fixed. You get on where you can get on, get off where you can get off, and share expenses with other users of the same route. The private car, on the other hand, responds to a specific request for a route not covered by any other means (or it does, but the alternative means are preferred for N reasons). This absence of a fixed and shareable structure is the responsibility of the person who calls the car agency and prays that they do not get the crappy car with no A/C and a debatable rear shock absorber performance.

Having this context in mind, considering that a freighter will charge the same for an already established service as for one it has to put together from scratch (with all the logistical considerations it has, plus the detail that the two connecting points are no less than 13,500 kilometers apart) is just unfeasible. Even more at this pandemic situation where belly cargo (cargo capacity that is leveraged on scheduled commercial passenger flights) almost disappeared – when it completely disappeared, in May 2020, the TAC index was way up from what it is today – and therefore dedicated freighters are making a significant economic difference. They are obviously not doing too badly.

Another important detail is that the cost indicated by the TAC index is based on the perfection of the system: I take my merchandise up, I take it down and I pay exclusively the cost of what was on the plane. Unfortunately, on routes outside the established city pairs, this is not realistic. Any freighter doing this route will charge – if no customer carries it with cargo – empty from origin to origin, from origin to destination with cargo and charge empty return to the first point where it has cargo to pick up and carry.

For example, Volga-Dnepr will be able to do Ulyanovsk (its operational base) – Sheremetyevo with another customer’s cargo, unload it, load the vaccines with destination Ezeiza, arrive, unload, and leave for Lima, where another customer’s shipment will be waiting to take it to its base or to its previously defined routes. The excellent scenario is where you share cargo. However for sections that you have to travel empty… will be in charge of the client who hires you. This brings us to the third problem.

3- The complexity of the cargo affects the transportation mode. The logistics decision for vaccine distribution has two key components:

a. There is no choice to point-to-point transportation: Due to the perishable, sensitive, limited nature of vaccines and their transportation conditions, vaccine logistics cannot be done by taking advantage of a hub structure. IATA, in its Guidance for Vaccine and Pharmaceutical Logistics and Distribution document, last revised in December 2020, identifies among the challenges of vaccine distribution:

These two factors -safety and infrastructure- indicate that transport must avoid any unnecessary delays, deviations, and waiting times.

Last October, the European Union determined in its document Preparedness for COVID-19 vaccination strategies and vaccine deployment that the distribution of vaccines will be made from the manufacturer to each national hub and that internal distribution for vaccination will be the responsibility of the member state. This means that there will be no regional hubs or collection centers. Point-to-point distribution.

DHL, in its document Providing Pandemic Resilience, identifies three scenarios for vaccine distribution, depending on the conditions of the vaccine and the distance from the manufacturing center to the vaccination point. For the Argentine case, the solution archetype described is number 3.

However, none of these three scenarios involves transportation through hubs, but rather a point-to-point air connection between the origin closest to the manufacture of the vaccine and the destination closest to the local handling of the goods and final distribution.

Indeed, all shipments made by DHL have worked in this way, and the Pfizer chain is currently managed under these conditions, with the distribution center in the United States to serve the American continent and the hub in Belgium for Europe and the rest of the world.

b. The health priority of a scarce good is more important than the economic convenience of its logistics:

This basically means that, regardless of cost, if there are 240,000 doses ready to be brought in, 240,000 doses will be picked up. It has just been done, and while it is clear that it is not ideal and that it is always better to get a million per flight, nothing seems to indicate that it will not be done. It is a State decision, and not only from this one: Chile received the first shipment of 10,000 doses. Bolivia, 20,000. Mexico, 10,000. Pfizer’s first shipment to Israel was 4,000 doses. The decision is a health one, not a logistical one. And it must be.

Chile received two million doses of Sinovac in a week, which is an excellent use of capacities and of the storage and transport conditions of this specific vaccine, with lower cold chain requirements. But the conditions of Pfizer/Moderna, AZ, and Sputnik-V itself are not so benevolent. And that makes a big difference. At the same time, I did not find a single example of a government deciding to defer the reception of vaccines while waiting to optimize the economic cost of their shipping.

4- Then, what is the cost of a freighter: If according to what we explained in point 2, we must discard a TAC Index of 7.66 (the one of 4.05 was discarded in point 1), we still need to know what is a valid cost for the route we are interested in. That would be, how much a freighter will cost us to do what we need it to do. Let us get back to a key and very «capitalist» detail: the greater the demand, the greater the pressure on the price.

In December 2020, WHO’s Head of Logistics and Operations Support, Paul Molinaro, told Reuters that one of the world’s logistics giants -whom he preferred not to name, so if WHO’s logistics Chief has that respect, we know it’s a big one- asked him for $105 per kilo of goods transported between Dallas (USA) and Sierra Leone. 105 dollars. To be charged to the World Health Organization.

We can apply the same index, but it would not really tell the whole story: as we said before, the TAC Index is the expression of a perfect cargo transport scenario and it does not take into account all the empty movement of the airplane, which obviously also has a cost.

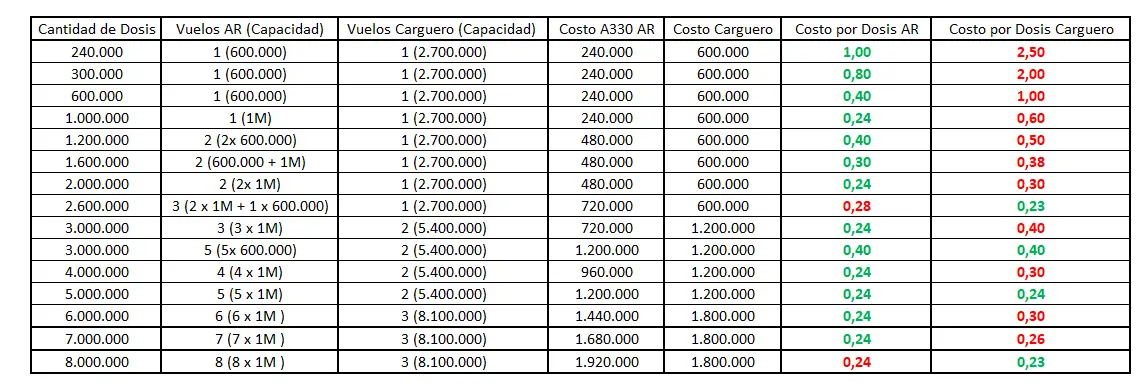

So, what is a valid cost measure that we could safely consider for the operation? Quite simple: divide the operating cost of an airplane by the number of doses it transports on that flight. Let’s forget about the cost per kilo and just look at the cost per dose. We will return to the cost per kilo transported in Part 2.

So, keeping in mind:

- That the number of doses available is a variable value,

- That the maximum capacity of an Aerolíneas Argentinas A330-200 is 600,000 doses in the hold and one million removing the center row of cabin seats,

- That we can establish an approximate freight value, based on an average of quotations for the route provided by some of the operators with the technical and operational capacity to perform it, of about 600,000 dollars per flight for a large freighter aircraft; and

- That, from a simple calculation, we can establish a maximum capacity for that freighter of $600,000 per flight. We determine that the A330-200 can carry 600,000 doses in 8 pallets in the hold, and we know that a 747-400F can carry 27 pallets of the same size in the main cabin and 9 extra pallets in the lower hold. Let’s do the math: each pallet of Sputnik-V will carry 75,000 doses. If we multiply that value by 36 pallets, we will have a maximum capacity of 2,700,000 doses per flight. But there is a limiting factor that makes it impossible to reach that total: the amount of dry ice on board. We explain it in this article:

We just need now establish the cost per dose that each trip actually brings, in accordance with what we said in point 3-b: the doses that are made available will be fetched. Under these conditions, there is no mathematical plot twist: $240,000 per flight is less than $600,000 per flight. Therefore, as long as the operating value of Aerolineas’ individual flights does not exceed the operating value of the freighter’s individual flights, it will be cheaper to operate own equipment, and only in some configurations which are far from the maximum amount of doses that the sum of existing capacities can handle and closer to the freighter’s maximum capacity, a cargo flight makes sense.

It is quite a bit clearer in this chart:

So now with all the available data, we can affirm that for the volumes of cargo that can be handled and trying to take advantage of each trip using the best available configuration to bring as many doses as possible, the most reasonable option is still to use our own metal. In other words: No, a freighter is not cheaper.

It gets rough if we have to go for 220,000 vaccines, of course, it does. But on one hand, the logistics of «Let’s see as we go along» which is imposed for this situation of massive demand and scarce proportional production, leads to that. It would be ideal to fetch a million doses per flight. This will not always be possible, and such a decision will not depend on the operator. It will be more important for the production laboratory and the forwarder who prepares the shipment than the final carrier. In the «We’ll see» dance, sometimes it is necessary to close the discussion with a loud «It is what it is».

The question we are going to ask ourselves and answer in Part 2 is the following: What is the operational limit of the effort to bring in 15 million vaccines, as expected for February and not counting the pending ones for this January that is coming to an end? As we have already seen, it depends on the number of vaccines made available per delivery, but we are also going to analyze the technical and human capacities available for the logistical bridge. Again, comparing with a dedicated freighter in the specific operating conditions of the route.

As we will see, there is more than one scenario where a dedicated freighter can and will eventually be needed. And again, if the strategic decision is to ensure the availability of vaccines above logistical convenience, we will have to take these costs into account.