At a time when the skies remained an uncharted frontier for humanity, a child was born who would forever change mankind’s relationship with aviation: Charles Augustus Lindbergh. Today, on the 123rd anniversary of his birth (February 4, 1902), we look back at the life, milestones, and complex legacy of this American icon. His solo transatlantic flight in 1927 not only made him a legend but also accelerated the development of modern commercial and military aviation.

Early Life and Passion for Mechanics

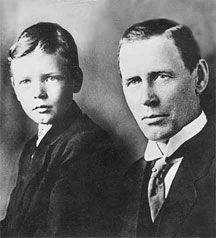

Lindbergh grew up in Minnesota, the son of a congressman and a chemistry teacher. From an early age, he showed a fascination for mechanics—disassembling tractor engines and building a rudimentary wooden airplane at just 10 years old. However, his true passion took flight in 1922 when he dropped out of mechanical engineering school to become a barnstormer pilot, performing aerial stunts at traveling air shows.

In 1924, he joined the U.S. Army Air Corps, where he graduated as a military pilot. Shortly after, he worked as an airmail pilot on the Chicago–St. Louis route, honing his skills in extreme conditions. "Airmail was an unparalleled flight school. I learned to trust my instruments when visibility was zero," he later wrote.

The Challenge That Made Him Immortal: New York to Paris, 1927

In 1919, French hotelier Raymond Orteig offered a $25,000 prize (equivalent to around $400,000 in 2025) to the first aviator to complete a non-stop flight between New York and Paris. By 1927, several teams were competing for the reward, but multiple tragedies—such as the disappearance of French pilots Nungesser and Coli—cast doubts on the challenge’s feasibility.

At just 25 years old, the then-unknown Lindbergh convinced a group of St. Louis businessmen to fund the construction of a custom-built aircraft for the mission: the Spirit of St. Louis, manufactured by Ryan Airline Company in just 60 days. With a 223-horsepower Wright Whirlwind J-5C engine and fuel tanks occupying most of the cockpit (eliminating a front windshield to reduce weight), the monoplane was a daring gamble.

On May 20, 1927, Lindbergh took off from Roosevelt Field, Long Island. Over the next 33 hours and 30 minutes, he battled fog, wing icing, and extreme fatigue, navigating only by compass and the stars. Upon landing at Le Bourget Airport in Paris, a crowd of 150,000 people welcomed him as a hero. His achievement not only won him the Orteig Prize but also proved that aviation could unite continents.

"Lindbergh did more than cross an ocean—he brought the world closer together." His feat sparked massive investments in airlines such as Pan Am and TWA, and normalized the concept of transoceanic flights.

Lindbergh: Between Glory and Tragedy

The fame of the "Lone Eagle," as the press called him, came at a cost. In 1932, the kidnapping and murder of his 20-month-old son, Charles Lindbergh Jr., shocked the world. Known as "The Crime of the Century," the case led to the creation of the U.S. Federal Kidnapping Act and accelerated the use of aviation in police investigations.

During the 1930s, Lindbergh’s reputation suffered due to his sympathies toward Nazi Germany. After visiting the country in 1938, he received an award from Hermann Göring and advocated for U.S. neutrality regarding Hitler, aligning himself with the America First Committee, an isolationist movement. Though he later distanced himself from the Nazis during World War II—even flying combat missions in the Pacific—this chapter remains a controversial part of his biography.

Beyond the Spirit of St. Louis: An Aviation and Science Innovator

Lindbergh was more than just a record-breaking pilot—he was a relentless innovator. In 1929, he collaborated with surgeon Alexis Carrel to develop the first perfusion pump, a precursor to artificial hearts. As an advisor to Pan American World Airways, he also promoted the use of aircraft such as the Sikorsky S-42 for transpacific routes.

In his later years, he dedicated himself to environmental conservation, advocating for indigenous tribes and endangered species. "Technology without ethics is a threat to life," he stated in a 1968 speech. His work with the International Wildlife Foundation partially restored his public image.

Lindbergh’s Lasting Legacy

Lindbergh passed away in 1974, but his influence remains strong. His transatlantic flight inspired advancements in radio communications and navigation systems, while the Spirit of St. Louis paved the way for long-range aircraft like the Douglas DC-3. His Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Spirit of St. Louis (1954), helped popularize aviation culture.

Today, his legacy lives on in museums such as the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, where the Spirit of St. Louis hangs alongside the Wright Flyer and Apollo 11’s Lunar Module.

"He was a man of contradictions, but without him, commercial aviation would have taken decades longer to take off," says curator Dorothy Cochrane.

Comentarios

Para comentar, debés estar registrado

Por favor, iniciá sesión