The Wright Brothers’ First Flight: A 12-Second Leap That Changed the World Forever

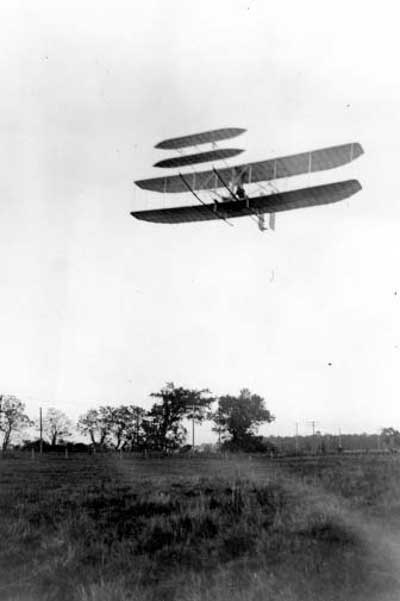

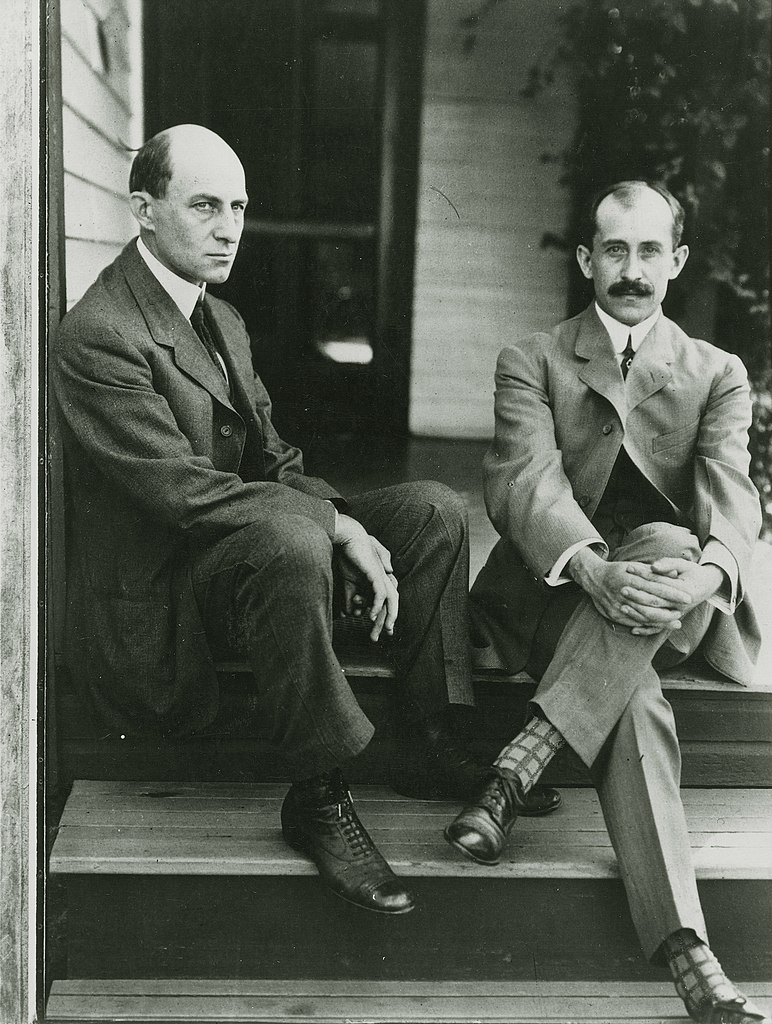

On December 17, 1903, on a cold morning in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, the world changed forever. What began as an improbable dream, the obsession of two brothers who built bicycles for a living, culminated in 12 historic seconds. Orville and Wilbur Wright achieved what no one else had before: powered flight.

Though the first flight covered a mere 120 feet, humanity crossed an invisible threshold between the possible and the impossible. This was not just a technical achievement—it was an act of unwavering determination and faith in the future. It was the moment humanity took its first step into the skies.

Building on the Shoulders of Pioneers

Orville and Wilbur Wright were not alone in their pursuit. The road to flight had been paved by pioneers who had dreamed and failed before them. The German glider pilot Otto Lilienthal, who conducted over 2,000 glider flights before dying in a crash, had proven that controlled gliding was achievable. His work inspired the Wrights to take flight from theory to practice.

Other minds, like British engineer George Cayley, had laid the foundations of aerodynamics as early as the early 1800s, defining key forces such as lift, drag, thrust, and gravity. Meanwhile, American inventor Samuel Langley had attempted powered flight but failed spectacularly, his aircraft plunging into the Potomac River. The Wrights learned from these efforts and failures, understanding that the true key to flight was control—mastering pitch, roll, and yaw.

Their genius was in combining observation, experimentation, and a deep respect for physics. Using their mechanical expertise, they designed a lightweight engine, constructed their Flyer I out of spruce wood and fabric, and developed a system of wing-warping for lateral control. What they achieved wasn’t just a flight—it was the first controlled, sustained, and powered flight, a feat that redefined what was possible.

The Day the World Took Off

On that December morning, the Wright brothers made four flights. The first, piloted by Orville, lasted 12 seconds and covered 120 feet. The final flight of the day, piloted by Wilbur, reached 852 feet in 59 seconds. The world had taken off, and there was no going back.

Yet, like all revolutionary achievements, their success was not without controversy. Across the Atlantic, the Brazilian aviator Alberto Santos Dumont was making his own mark on aviation history. In 1906, Santos Dumont publicly demonstrated the first airplane to take off unaided by catapults or rails: the 14-bis in Paris. This led to debates over who truly achieved the “first flight.” Supporters of the Wrights emphasize that their controlled, powered flight in 1903 marked the true beginning of aviation, while others argue that Santos Dumont’s fully independent and public demonstration set a different milestone.

Regardless of the debate, both the Wright brothers and Santos Dumont shared a common ambition: to free humanity from the ground.

What Came After Kitty Hawk

The Wright brothers’ work did not stop with that historic flight in Kitty Hawk. Returning to their home in Dayton, Ohio, they set up a testing field at Huffman Prairie, where they perfected their aircraft. By 1905, the Flyer III could fly for over 39 minutes, covering miles at a time, making it the first practical airplane in history.

Yet the world was slow to embrace their achievement. Protective of their innovations, the Wrights sought patents and refused to share details, leading many to dismiss their claims. Recognition finally came in 1908, when Orville demonstrated their aircraft in the United States and Wilbur stunned audiences in France with public flights that proved their mastery of powered flight.

Wilbur, the older of the two, became the face of their work in Europe, while Orville continued testing and improving the aircraft back home. By 1909, the Wright brothers had founded the Wright Company, building and selling airplanes to governments and private buyers.

A Bittersweet Legacy

Wilbur’s life was cut tragically short in 1912, when he succumbed to typhoid fever at the age of 45. His death marked the end of an era for the Wright brothers’ partnership. Orville continued to advance their legacy, though he eventually sold the Wright Company in 1915. He became an advisor and respected figure in aviation, witnessing firsthand the rapid progress his and Wilbur’s work had set in motion.

Orville lived to see aviation evolve into something beyond their wildest dreams. By the time of his death in 1948, airplanes were flying faster and farther than ever imagined, and the jet age had already begun. The humble Flyer I, made of wood and fabric, had become the ancestor of machines that connected continents, shaped history, and even carried humans into space.

A Legacy That Still Soars

The story of the Wright brothers is a testament to humanity’s capacity for greatness. It is a reminder that, with curiosity, perseverance, and the willingness to challenge the unknown, we can transcend limitations. Today, 121 years later, aviation carries over 10 million people daily across the globe, shrinking distances and uniting worlds.

While debat

es over pioneers like Santos Dumont persist, the undeniable truth is this: powered flight was born from human ingenuity and the courage to dream. Orville and Wilbur’s fragile Flyer I was more than an invention—it was the spark that ignited the century of flight.

To the Wright brothers—and to all dreamers who look to the sky—thank you for showing us that the sky is not the limit.

Happy Anniversary, Wright Flyer. Thank you for teaching us to fly.

Para comentar, debés estar registradoPor favor, iniciá sesión