Never-ending nightmare: Boeing lost 1.2 billion in 2022 first quarter

As if it were becoming impossible to climb out of the hole, Boeing lost again. It started 2022 still trying to come to terms with three years of debacle and with the 737 MAX already certified, but with 787s piling up in the factory and on the books.

With a 777X program that is far from achieving certification and with a 737-10 that has a clock ticking so as not to be left out of the current process of obtaining its type certificate, a detail that is fundamental because in 2023 it will require authorization from Congress or start the process all over again.

With Defense programs, a department that has always been an inexhaustible source of income, which has both problems and expenses. With two 747s destined to be the new presidential transports that were negotiated with an implacable Trump, and which were only going to be profitable if everything went well.

And lately, for Boeing, things have not been going well.

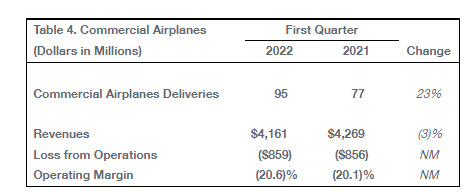

Boeing Commercial: more planes delivered, more losses

Beyond having increased to ninety-five the number of aircraft delivered in the first quarter when compared to 2021, today the reality of the area is one: without widebodies, the equation does not close.

In the first quarter of 2022, Boeing Commercial lost $859 million, $3 million more than in the same period of 2021, even though it delivered eighteen more aircraft. The company says the war in Ukraine and «higher research and development costs» impacted operating margin.

Adding to that impact will be the 777X debacle: the factory has confirmed that it will halt production until 2023, adding $1.5 billion to the total cost of the program.

Boeing also indicated that it has already submitted the 787 recertification plan to the FAA, and production will remain at a «very low» rate until deliveries are authorized. Thereafter, the goal is to gradually reach production of five aircraft per month.

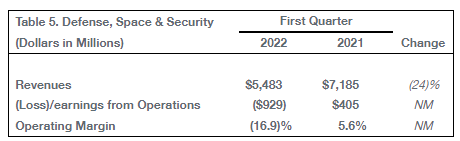

Defense, Space & Security: the party is over

The quarter of a division that kept the manufacturer going during the Commercial debacle of recent years was abrupt and cruel: after making $405 million profit in 2021, in 2022 Boeing lost almost $1 billion.

For Boeing, $660 million of that loss is on the VC-25B program, the replacement for the 747-200s modified to be presidential jets. The two planes are being assembled in San Antonio, Texas, but are far from completion, delivery and – even worse – profitability for the manufacturer.

This is not the first additional charge the program has taken on: in April 2020, it had already declared it would cost 168 million for «engineering inefficiencies» caused by the pandemic; in May 2021 it added another 318 million for «performance issues» from a supplier: GDC Technics, which received a lawsuit and contract cancellation from Boeing, went bankrupt and ended up filing a countersuit.

So far, the VC-25B program is 1.1 billion over budget, more than a quarter of what the fixed-price contract signed with the USAF called for: 3.9 billion. There is little margin – if any – for Boeing not to end up delivering the two aircraft at a loss.

William Calhoun, the current CEO, confessed at the post-earnings press conference that the negotiation for these two aircraft was not the best.

«I’m going to call it [the Air Force One deal] a very unique moment, a very unique negotiation, a very unique set of risks that Boeing probably shouldn’t have taken,» he said. «But we are where we are, and we’re going to deliver great airplanes. And we’re going to recognize the costs associated with it.»

Add to the VC-25B costs a classic: 165 million in charges on the KC-46 program, which must be credited with a singular consistency: it never fails to make a loss. This time, «higher supplier and other costs» were added.

But two fresh players also entered the cost overruns game: the T-7A Red Hawk, at $367 million, and the MQ-25 Stingray, at $78 million. In the case of the Red Hawk, negotiations with suppliers were complicated by «supply chain issues, COVID-19 and inflationary pressure».

For the Stingray, the additional costs relate to «supplier quality challenges» and «additional customer testing requirements.»

What is the big challenge? Surviving the extra costs with one small detail: all four contracts – VC-25B, KC-46A, MQ-25 and T-7A – were signed at a fixed price, which prevents passing those costs on to the customer. Perhaps, the departure of Leanne Caret announced at the end of March had more to do with these negotiations than the graceful retirement indicated in the communiqués.

It is true that the outlook for the second quarter looks a little better: with the E-7 Wedgetail and the German Chinooks just closed, the Defense division’s cash flow should improve. But the mediocre performance of what until now has been a safe business is striking.

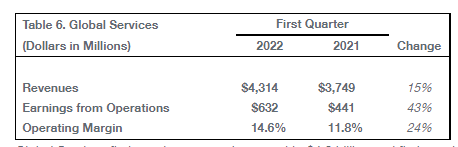

Global Services: The old, reliable division

At least one Boeing division performed well: after-sales management was able to close a quarter in the green, with a net profit of $632 million. Part of this success can be explained by the booming freighter conversion contracts and the recovery of the global airline market, which is driving increased use of existing capacity.

It is difficult to imagine the scenario that awaits Boeing in 2022 and the years to come. New products are postponed, current ones are in trouble, the stock is falling and there is no easy solution in the short term. It remains to be seen what else happens at this stage for a giant that is not just sleeping. It is not dreaming pretty.

Para comentar, debés estar registradoPor favor, iniciá sesión