A quick search on the internet will show you one of the obsessions of the Workers’ Party’s (PT) agenda; that in their government, o pobre andava de avião — literally, «the poor traveled by plane».

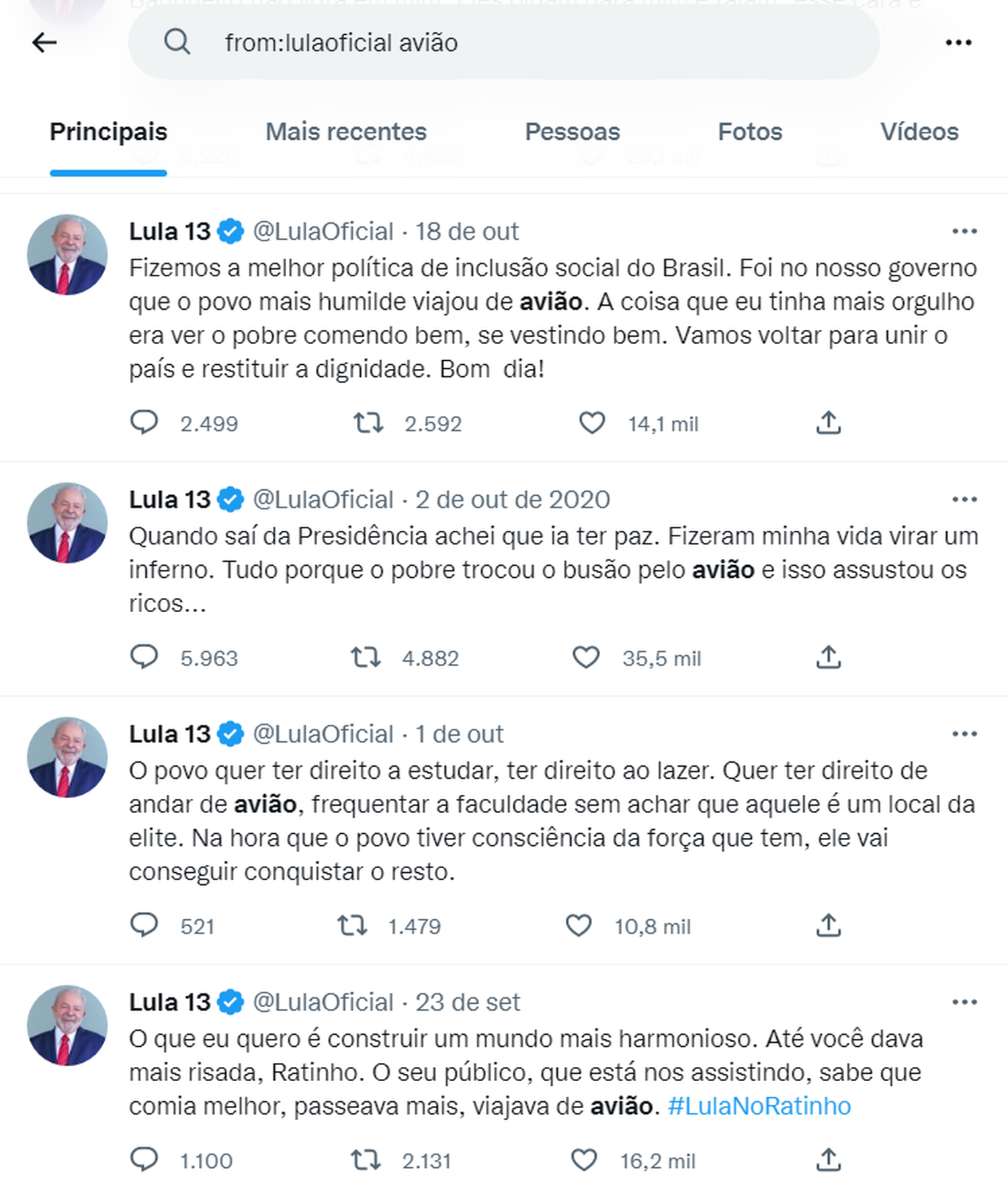

Now that Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was elected, for the third time, for the highest seat in the Republic, the party’s supporters are hopeful that these «times» will return. In fact, if you search it up on Lula’s Twitter profile you will find out that he mentioned this same allegory a total of forty-five times.

Of course, statistics show that the Lula years were a very prolific period for air travel in Brazil; the graph below shows the number of paid passengers in Brazil (domestic and international). Lula was President from 2003 to 2011, and his successor, Dilma Rousseff, led the country from 2012 to mid-2016, when she was ousted in a political crisis largely fueled by the second largest recession in the country’s history.

Still, Lula’s times are still widely seen as an economic bonanza in the country’s history — after all, that may explain in part how he got elected again –, and the massification of air travel is a huge driver in that narrative. But how did Lula handle the aviation sector in his eight years as president of the Republic — and what to expect next?

The aviation market in Brazil from 2003 to 2010

With the commodities boom in the early 2000s and monetary stability after the Plano Real in 1994, Brazil started to experience serious economic growth.

This, alongside the deregulation measures ongoing from 1989 which culminated with the end of fare controls in 2001, made the market perfect for new entrants. And by that, we mean low-cost entrants.

Amongst many that didn’t survive the competitive scenario, the one that grew the most was Gol.

The airline made headlines from the start, with its low fares and its barebones product. And it worked. And the deregulation process continued: as the LCC model marched on, Transbrasil had already gone bust in 2000, and during Lula’s government VASP failed in early 2005 and the most important of the three, Varig, failed a year later.

But Lula’s administration went on during a period of irreversible change in the airline industry nationally; and it was not up to the government to change it. Those who were not efficient went bust, and those who were survived, did it largely without government support. Lula’s policy was just a continuation of the non-intervention approach started by previous administrations.

Lula’s policy in commercial aviation

This, however, does not mean that his government did not have a say in business affairs in the airline industry. Already from the start, on early 2003, his subordinates articulated at his request a codeshare agreement between TAM and VARIG.

” The [agreement] is intermediated by the Minister of Defense, José Viegas», said a report by Folha de São Paulo at the time, «who has been deployed by the Lula administration to treat the Brazilian airline industry’s woes».

Such agreement, supported by the Federal government, had a clear scope: by rationalizing supply, to stabilize the situation of Varig, who was swallowed in a spiral of debt. Ultimately, the idea was to merge the two airlines if everything went well.

However, Varig was a victim of itself; its heavily bureaucratic structure, that effectively impeded change, sealed its fate. The codeshare agreement collapsed two years later after a ruling of the country’s anti-trust body, Cade, against the partnership.

And as for Varig, this is the reason the company’s «widows» have never forgiven Lula and PT; the government washed its hands after the company lost control until it collapsed, in 2006. To this day, it is almost a consensus amongst Varig’s apologists said that «o Lula deixou a Varig quebrar» (lit. «Lula let Varig go bust»).

But the truth is, such an interventionist policy would have opened a very dangerous precedent in Brazilian markets. First, Varig had dug its own grave over the years and it did not adapt to the new times and to an open market. Secondly, it had already shrunk enough to be negligible in the domestic market.

In a 2006 editorial in his industry leading «Jetsite», Gianfranco Beting, one of the country’s most prestigious aviation executives, defines the demise of Varig: «it’s worth remembering that Varig has got, today, not even 15% of the domestic market, it does not serve any market exclusively, it does not dominate any route. Varig’s demise will be a [mere] sneeze in the national tourism market, not a double pneumonia.»

And as President Lula said to journalists in April 2006, «it’s not up to the government to save [a] failed company […] Varig has a judicial agreement it has to meet. If [someone] is to solve, it’s not the government. For that, there are other instances, such as the Bankruptcy Law».

Lula was right: the Bankruptcy Law, signed under his watch on early 2005, was developed with the airlines (Varig included) in mind, Folha reported at the time. And Varig was the first major case to request the new model of bankruptcy, months later.

The case culminated with the sale of the «good part» of Varig to a consortium headed by the investment fund MatlinPatterson, in. The «nova Varig» (new Varig), free of most of its debt, was sold in July 2006. The «velha Varig» (old Varig), now renamed «Flex», remained operating charter flights with a single 737-300 until its liquidation in 2010.

Another major crisis — and this time, likely caused by themselves — Lula’s government faced was the apagão aéreo (air blackout) or caos aéreo in 2006, triggered by the crash of a Gol 737-800 in the middle of the Amazon.

The failures of the national air traffic control system were exposed by the accident, causing unrest within the ATC operators, huge disruptions in service, and thousands of delays.

Such issues extended into the Christmas period and into 2007, culminating, in July, with a TAM Airbus A320 overshooting the runway in São Paulo’s Congonhas Airport and crashing into a building across the avenue, killing 199 people in what was, and still is, the largest aeronautic accident ever to happen in Brazilian soil.

The accident caused national commotion, and Lula went to TV and radio to speak about it and to announce immediate measures to curb the air crisis. Beyond the safety upgrades, the most relevant measure, and one that reverberates to this day, was the reduction of operations in Congonhas. Lula also fired the Minister of Defense, Waldir Pires, who had up to that point managed to survive the havoc.

Congonhas, the most important domestic airport in the country, remains very prized by airlines; its very central position, close to the financial center of South America’s largest city, is compensated by high yields for airlines. And that, of course, is exacerbated to this day by the restrictions in capacity.

The problem eventually subsided by September 2007, but the chaos remains one of Lula’s worst moments during his presidency, even though his poll ratings showed otherwise.

In numbers, the more the country’s output grew and the more income was redistributed, the more people changed the bus for the plane.

This reflected in the level of fares. Barring 2008 (when the market was largely unchallenged by GOL and TAM), they all fell, in real terms, according to historical data by Anac, which can be observed below.

This steadily growing demand, allied to a duopoly that would eventually drive fares up — as it did in 2008 — made the market perfect for new entrants.

2007 saw the entry in the market by one of the industry’s heavyweights, CVC (the country’s largest tour operator). The company took over a small airline from Rio, Webjet, and immediately, started scaling it up.

At its peak, Webjet operated 27 Boeing 737-300, charging very low fares with a very competitive cost structure; the company had been turned around with the help of Irelandia Aviation (the investment fund owned by the Ryan family) and Charlie Clifton, an early associate at Ryanair.

Its fares were at many times rock bottom. Many people, in fact, still remember the company with nostalgia as «the last true low-cost carrier in Brazil». The airline was taken over by Gol in 2011 and shut down a year later.

2007 was also the year where an airline that had been growing steadily for several years, went from heaven to hell: BRA, acronym for «Brasil Rodo Aéreo».

The airline, which had started as a «charter» carrier some years prior, received an injection from an investment fund, Brazil Air Partners, and it had big plans. So much so that, in August 2007, the airline signed an agreement for 20 Embraer E195. The event in São José dos Campos had a prestigious guest: President Lula.

«The move BRA is making will be repeated by other companies», predicted the President in the event, according to Folha.

Less than three months later, over fights between the fund and the founders of the airline, BRA went bust. But there was another big player eyeing the Brazilian market — and he was contemplating doing so through BRA.

Serial airline entrepeneur David Neeleman ultimately did not made a move into BRA, but Azul operated its first revenue flight in December 2008 — and operating more or less the same business model the demised carrier would have, had it continued its flights.

The airline, initially, operated only Embraer E-Jets, but after that, it diversified its fleet — but that’s not the point of this article.

What matters is that whether you like him or not, under Lula commercial aviation in Brazil saw the greatest leap in its history. There was the caos aéreo, but ultimately, the structural cause of those troubled months was the neck-breaking growth of flights — the structure of Brazil’s aviation system was just not prepared for it.

But how about military aviation?

The FX-2 program

In the runoffs last October, during the first debate between President Jair Bolsonaro and Lula, the ex-President (now President-elect) spoke about Bolsonaro’s years as a Federal Deputy, where he figured as a interest group corporatist for the Armed Forces.

«He didn’t [ever speak against me in Congress]. You know why? Because deep there», said Lula, «he knows I was the President […] who took the most care of the Armed Forces. The Air Force didn’t have a plane […] and I gave [them].»

Technically, this is not untrue. Lula did order a plane for the Air Force: the presidential aircraft, an Airbus A319, which became popularly known (especially by the opposition) as the AeroLula.

It was a needed change, as the previous presidential aircraft was popularly known as the Sucatão (lit. «big scrap»), a Boeing 707.

But beyond the GTE, the Brazilian Air Force unit that operates flights for the President and other authorities of the Republic, government Lula was less smooth as far as aircraft selection goes.

The Brazilian Air Force entered the Century with a very old fleet of supersonic fighters, composed by the Mirage 2000s and the F-5s. As such, it needed a replacement.

In 2008 the Brazilian Government thus officially opened the FX-2 program, which would decide the next-generation fighter jet for the Brazilian Air Force.

A year later, a major blunder: Lula said that he had agreed to a deal with French president Nicolas Sarkozy for 36 Dassault Rafale, only for the government to scramble itself saying that actually, that was only a «negotiation with one of the suppliers», said the Minister for Foreign Relations Celso Amorim at the time.

Key to the decision of the Brazilian government was the complete transfer of technology from the original manufacturer to Brazil, a matter more of sovereignty than of economical logic and/or efficiency.

Ultimately, Lula kept delaying any announcement over the jet, and left it to his successor, President Dilma Rousseff, in 2013 — spoiler: the decision was for Sweden’s Saab Gripen, the first two of which were only received this year.

What to expect for the next government?

To better understand what aviation can expect from Lula in his third government, look no further than the shares of the airlines at the São Paulo stock exchange.

Both Azul and Gol saw a great increase in stock prices this week (the first after the election happened). Azul’s finished last week at BRL14.65, ending Friday at BRL16.14. Meanwhile, Gol’s finished last week at BRL8.70, ending Friday at BRL9.95; as of December 4th, 2022, BRL1 is worth USD0.20.

That’s because, analysts say, the next government will again be very focused on boosting consumption. The consumptions stocks, jokingly called by the market «kit Lula», include airline stocks.

Macroeconomically, 2023 will be a tough year, as the government inherits from the Bolsonaro government the deanchoring of spending at the inflation level (the spending ceiling). And with the debt-to-GDP ratio of the Federal Government having broken the symbolic 100% line, further spending will be closely followed by investors.

Still, Lula’s government is expected to be a center-leaning «national union» coalition, which has even seen Lula pledge fiscal responsibility and speculate on market names for his economical team.

And whether the «poor will travel by plane again», as Lula frequently says, remains to be seen. But the new times have apparently been well received by airline investors, who see their profit prospects grow.

Comentarios

Para comentar, debés estar registrado

Por favor, iniciá sesión