Analysis: why Norwegian’s Widerøe acquisition makes sense

Norwegian Air Shuttle made headlines this week as it announced the purchase of Widerøe, Norway’s third-largest airline by number of seats this year and the largest by number of departures.

While this name may not resound to the non-Norwegian ear, Widerøe is a household name nationally; it has been in the market for almost 90 years and is a lifeline for several communities far from the big centers, and for whom land transportation is most inconvenient or slow.

With that, Norwegian is offering NOK1.125 billion (EUR96.08 million as of July 9, 2023) for a controlling stake in the airline, which it claims values the company at NOK2 billion (EUR170.82 million). The price is still subject to change, the airline says in a press release, according to Widerøe’s profitability this year.

But after a failed experience in going astray from its business model with long-haul operations and even a brief venture in Argentina, one might ask why would Norwegian try doing something else again. After all, its «back to basics» approach has seemingly been working, as it focuses on the Nordics with an all-737 fleet.

Norwegian, however, believes the deal — expected to be closed by the end of this year — will be beneficial to the group.

Widerøe’s approach is fairly straightforward; with a fleet mainly composed of Dash 8 turboprops, to serve regional destinations in Norway, while also taking some minor international opportunities.

The domestic network, according to a presentation to investors published by Norwegian, has an important share composed of Public Service Obligation (PSO) flights. While these only represent 34% of its passengers and 20% of its ASK output, it represents 49% of all departures.

With such an important reach, the airline has 20% of the Norwegian market, but it has the monopoly into small communities.

Norwegian thus believes that adding Widerøe’s capacity into its system will have a positive effect into the rest of its network. In other words, a passenger departing from Brønnøysund will be able to depart in a Dash 8 and connect into one of its 737s into Southern Norway or other international destinations the low-cost carrier (LCC) serves.

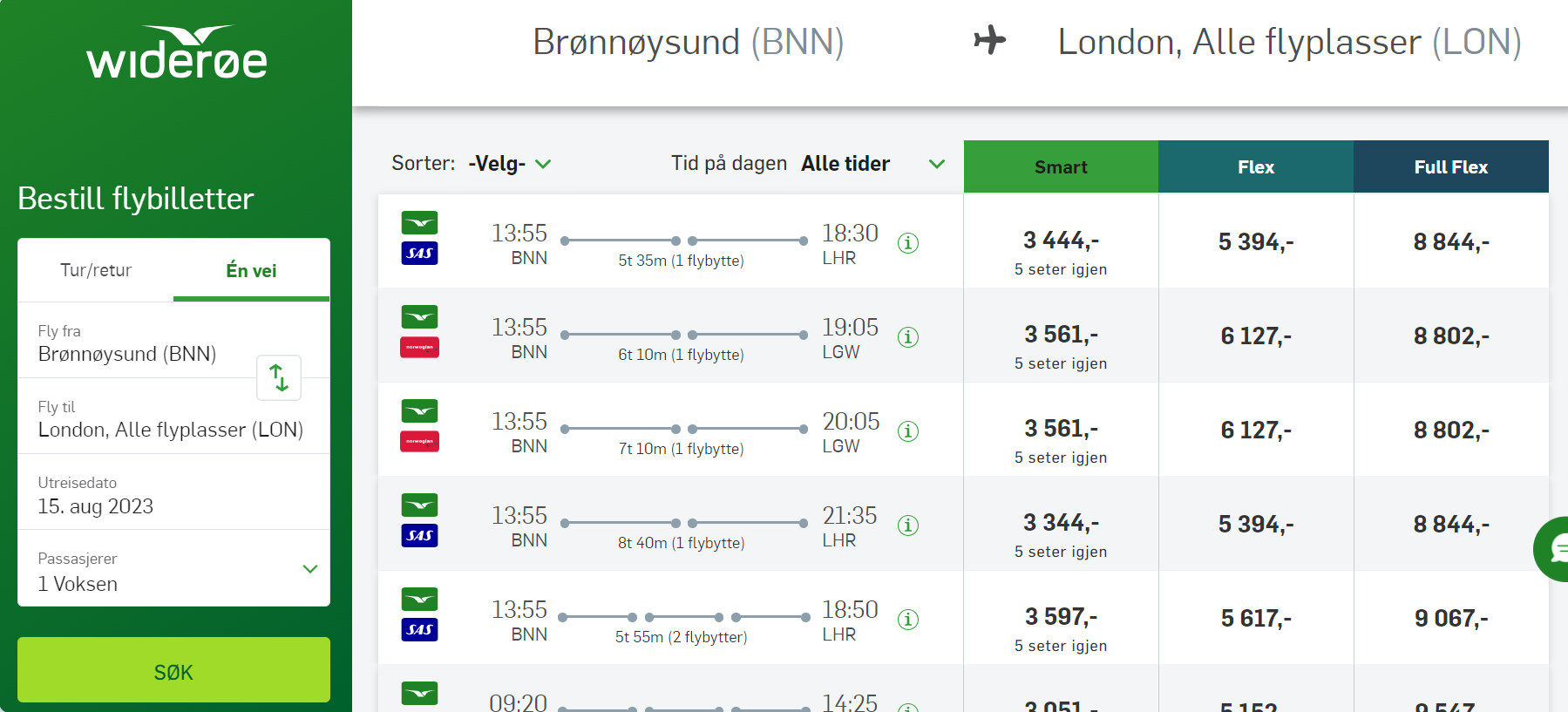

Such type of sale already happens at Widerøe’s sales channels, in fact; it sells connections with both Norwegian and SAS. However, Norwegian does not yet sell, in its website, connections to the regional carrier’s flights.

And according to Norwegian, given the very different natures of both airlines, this means that there is hardly any overlap between the two in terms of routes. According to the press release, out of the 107 domestic Norway routes both fly, there is overlap in five. Internationally, according to data by Cirium’s Diio Mi application, there is overlap in four.

Another very important aspect from the perspective of Norwegian is the seasonality. The presentation claims that Widerøe’s seasonality — the «relative max-min deviation from yearly average passenger number» is a fifth of the observed at the low-cost airline.

So incorporating the regional carrier into its system would bring a more constant stream of revenue, particularly with the PSO contracts, which only require reliability. It does not matter if the flight will carry one or 40 passengers, the flight will depart and the airline will be paid for it.

Norwegian said in the presentation synergies would amount, annually, to NOK200 to 300 million (EUR17.08 to 25.62 million). Despite «one-off implementation costs», the transaction is expected to be «highly accretive to earnings capacity» from 2024.

Thus, while this may add complexity to Norwegian’s main business model, it believes it is an efficient investment as it may even add some efficiency to Widerøe’s proposition, in a context where the regional airline is already mildly profitable. That is to say, it is already profitable, but it can improve its numbers with Norwegian’s market power, all while sensibly improving Norwegian’s footprint in its home country.

And the investment does make sense when put forward in this regional context. Perhaps the major question now would be whether Widerøe’s small fleet of three Embraer 190 E2, of which it was the maiden operator in the world, would be worth maintaining.

The E2 may give Widerøe more capacity in select routes, but domestically, there are no routes where it operates the majority of the airline’s frequencies, according to Cirium. Meanwhile, in nine international routes, it has the majority of frequencies, and in three of these it faces competition with Norwegian.

Still, in the other six, with the technical exception of Bergen and Sandefjord to Florence, Norwegian could eventually swap the E2 by its larger 737. If the airline could fill these flights with 76 more seats is another question, but it seems unlikely that having an entire different fleet for only a few routes would make sense financially.

And because this acquisition does not seem to have the scope of wiping a competitor out of the market, given the very limited level of overlap between the two, it seems that this is a combination that can work very well for Norwegian. This time again with added complexity, but a manageable (and profitable) one.

Para comentar, debés estar registradoPor favor, iniciá sesión